The lost art of work design

With each industrial revolution, work became increasingly mechanized. Supported by pop management theorists like Frederick Taylor[1], technology sought to take over organizations' production functions for the last 200 years. By and large, it succeeded. But rather than leaving workers without jobs, it created new ones.

As the nature of work evolves alongside technology, the human factor becomes difficult to ignore. Though I'm sure many managers and organizations agree with the sentiment, why is it they so often fail to act on it?

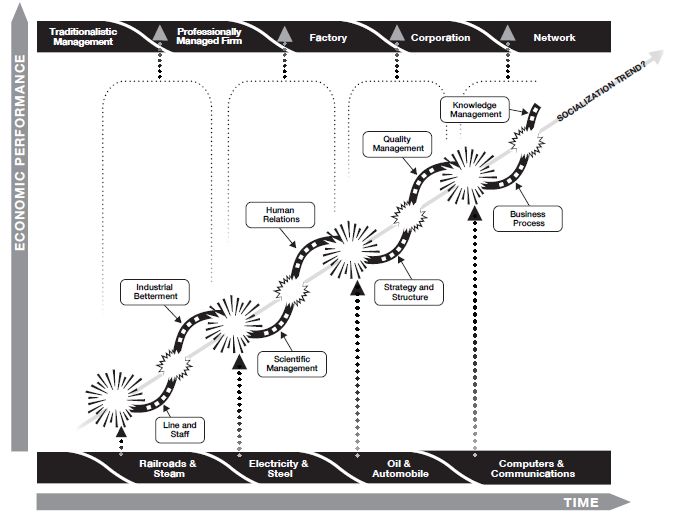

The evolution of management models provides some context:

For each revolution, whether it was tools or procedures, we've mechanized the way we work. Although scientific management may mark the peak of work mechanization, its ideals lived on. The human relations[2] approach attempted to consider the human element, but in practice, it mostly served to address low morale and high turnover resulting from these overly mechanized org structures.

The problem with these models is that they attempt to fulfill a pipe dream: that a one size fits all management model does exist.

In more ways than not, organizations across industries do share similar qualities and characteristics–which is why these models often result in improvements. But in reality, they were just an improvement over the last approach.

Like human beings, even with their many similarities, organizations are surprisingly unique. One could argue that each department and team is unique as well. And in turn, each contributes to the holistic uniqueness of the enterprise.

It is for this reason that one size fits all models will never be perfect. Yet high-performance work systems do exist. They reserve themselves for those who've found harmonious fit between the social and technical aspects of work.

A novel discovery

After World War II, a technological revolution in the coal mining industry primed a novel discovery for the organizational sciences. The story starts with Eric Trist, a researcher at the Tavistock Institute, who noticed that while some mining companies saw the productivity benefits of new technology, others did not. Even more puzzling was the fact that this seemed to be dependent on the companies date of establishment.

What could possibly be driving such a strange phenomenon?

Trist found a major difference in the way these companies organized their work. Depending on when the company was established, they took one of two approaches: production lines or workgroups.

The less established companies were founded with technology already embedded within their systems. The tech was similar to that used in factory work at the time and the work design reflected as much. Workers were assigned the simplest possible tasks and repeated them under the presence of supervisors.

In contrast, the well-established mining companies held on to legacy practices, limiting the use of technology. These miners worked in small teams called workgroups. They were self-regulated–working with minimal to no supervision. They swapped tasks and they learned each other's skills. Rather than doing a single piece of a much larger process, they saw the completion of the entire work process to the final product.

The most interesting thing about this case wasn't the differences in how they worked, but which differences predicted success with advanced technology. In contrast to expectations, it wasn't the organizations already accustomed to technology, but it was the workgroup organizations that saw all the benefits.

This led Trist to a simple yet novel discovery: performance is contingent upon both organization and technology.

The lost art of work design

One would expect that a group already accustomed to technology would have more easily adapted to new enhancements. But the opposite was true.

This problem goes deeper than technological exposure. The problem lies in the way the work was designed. The companies new to the game had adopted a production line organization where workers were assigned highly specialized tasks, limiting their ability as an organization to learn something new. Specialization limits adaptability.

The workgroup organizations on the other hand acted as generalists. They each learned multiple facets of the job and contributed to the entirety of the end product. Individual workers were much more attuned to the nuances of the system, they had a greater understanding of what worked and what didn't, and they were more easily able to pick up new skills, as had been part of their jobs prior.

A later finding from Trist's work was the workgroup organizations almost always outperformed production line organizations. Yet, the mechanized models like the latter were much more the norm.

One problem may be that instead of deciding how to best organize the work and then choosing new technology, most organizations adopt new technology and then try to re-organize the work around it.

Technology doesn't solve our problems, people do. Technology simply acts as the tools and procedures leveraged to achieve human desired outputs[3]. In order to design a high-performance work system, finding balance between the social and technical aspects of work is critical. Such a balance cannot be found by updating one aspect and not the other.

This is the idea behind the sociotechnical approach–a set of procedures for redesigning an organization for the best fit between social and technical subsystems. The result is a high commitment workforce: the precedent to a high-performance system.

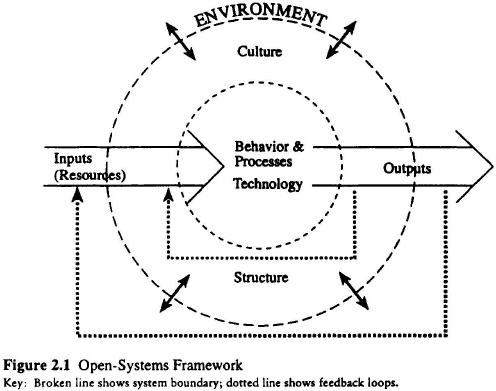

This starts with the view of the organization as an open system.

Organizations as open systems

In this view, the organization is a set of interrelated processes and elements which transform inputs into outputs while simultaneously interfacing with its environment.

Inputs refer to resources, which can be anything from materials to human beings and information. The system transforms those inputs into final products or services for customers, which represent the starting element to the feedback loop most organizations work towards: cash flow.

Organizations must act within the environment to achieve their goals. Money represents yet another input the system transforms into output [e.g., labor, materials, etc.] and is part of the transactional environment.

The transactional environment consists of agents the system must act with directly. Agents can be anything from employees, customers, and investors to other supply chain touchpoints. When resources must be extracted from the environment, such as in the coal mining industry, they may also be considered part of the transactional environment.

Then, there are those elements that indirectly affect the system. This is the contextual environment. It includes things such as regulatory constraints and technical limitations.

These elements of the environment that act both directly and indirectly and both inside and outside of the system are the organization's domain.

The sociotechnical approach

The sociotechnical approach aims to consider all aspects of the open system and its domain in designing the work. The goal is to design a system that can get from input to output with as few errors and iterations as possible.

All parts of the organization play a role in the conversion process. Like other systems, work systems are self-regulating–able to sustain themselves via feedback loops and without excessive supervision through the power of shared goals.

Yet few organizations allow themselves to operate this way. Almost as though some innate human fear has blocked the power of a shared vision from being the sole regulating authority over collective goals. Instead, most organizations abide by traditional hierarchical models, task specialization, and functional optimization leading to the same old broken bureaucratic enterprise.

This is where the sociotechnical approach comes in–leveraging the hidden superpowers of open systems: that they can be self-regulating, that they can create feedback loops, that they can achieve states of equilibrium. All through the connective power of shared goals.

What defines the sociotechnical approach is its emphasis on the social and technical subsystems and its attempt to find harmony between them. The two are the heart of the conversion process. While the social subsystem defines who does the work, the technical subsystem defines how. Often, inefficiencies are a result of their misalignment.

When the production line coal miners failed to reap the benefits of new technology, it wasn't just natural human resistance to change. It was the fact that the social dynamics of the work were not supported by the new technical aspects of it. And because these miners completed a single specialized task in the conversion process, having them adopt new tech required a completely new set of skills. Whereas the workgroup organizations were cross-functional. Having been accustomed to a diverse skill set, they simply needed to build on top of it.

But finding the perfect fit between social and technical subsystems is no easy task. It takes commitment, coordination, collaboration, and consensus[4]. New teams must be formed to critically analyze the work system from diverse perspectives. The first goal of this team is to agree on a shared picture of the system.

It is only when we have these features that an authentic, collaborative effort towards improvement becomes attainable.

This post is part of a series on the sociotechnical approach.

Footnotes

- Taylor pioneered scientific management alongside his work in industrial engineering. There is much overlap between the two.

- Both human relations and the sociotechnical approach gained influenced from overlapping forces [e.g., Tavistock, Hawthorn studies, etc.] However, the human relations approach represents an increased emphasis on the human element of work while the sociotechnical approach is about designing a custom model based on the best fit between social and technical subsystems.

- This ignores the theoretical potential for artificial intelligence to solve problems on its own. Yet today, most A.I. and machine learning models used in organizations require human development, maintenance, and input.

- I call these the four C's of sociotechnical design teams.