Job diagnostics and the motivation equation

In Jobs, Race Cars, and the Designer's Paradox I wrote about the nature of job design and how we should think of jobs like Formula 1 cars:

"...the safety and well-being of the driver is an ancillary consideration to winning the race. In other words, you can't win a race with a dead driver."

Most of the time though, we won't be doing the designing in the first place; like being given a hunk of scrap metal and asked to find someone to get in the cockpit.

The problem is, we've committed to this race. No matter how bad the job, we still need to fill it.

To this regard, we ought to be fixing up that hunk of scrap metal as best we can. Given the opportunity, we should work to craft jobs that are rewarding and provide people with the tools they need to succeed. When we do this well, we maximize motivating potential.

Measuring Motivation

Back in the 1970s, Richard Hackman and Greg Oldham developed a protocol for measuring a job's capacity to motivate: the job diagnostic survey. A parallel assessment to their job characteristics model, which remains one of the most widely accepted theories in I/O psychology.

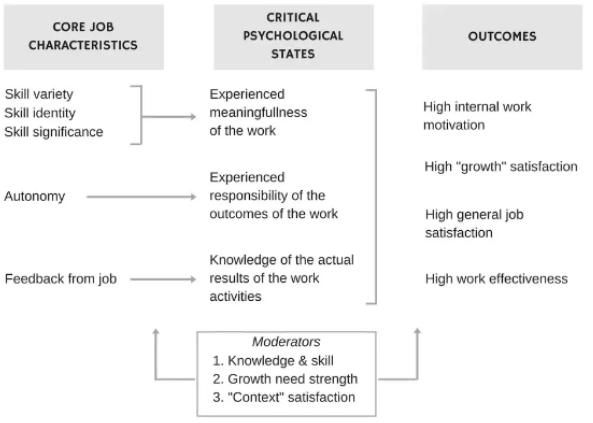

Based on the idea that the task itself is the key to motivation, the job characteristics model outlines five job characteristics that influence three psychological states contributing to the employee experience. Ultimately these psychological states mediate desired outcomes, such as performance and organizational commitment[1].

The five job characteristics:

- skill variety: the range of tasks performed

- task identity: the degree to which the whole job is completed from start to finish [i.e., are they building the whole car or just desiging the tires]

- task significance: the impact the job has on others

- feedback: the degree to which knowledge of performance is learned

- autonomy: the degree of discretion and freedom over the work

It is the designer's job to moderate the connections between job characteristics and psychological states.

The psychological states:

-

experienced meaningfulness: the degree to which the worker experiences the work to be inherently meaningful or valuable to them

-

experienced responsibility: the degree to which the worker experiences a feeling of responsibility for the work

-

knowledge of results: the level of clarity and direction the worker has about outcomes of a response in relation to a goal

These psychological states mediate the outcomes on the right hand of the figure above. Said differently, they are the reason those outcomes happen. This is an important aspect to understand because the job characteristics themselves do not result in these outcomes. Rather, the worker's psychological state does.

This implies that different workers produce different outcomes [and have different needs as well].

To maximize the likelihood that these psychological states are reached, we need a way to measure our baseline. Luckily, Hackman and Oldham, yet again, give us just the thing:

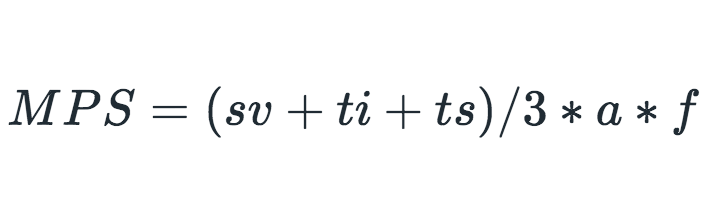

Motivating Potential Score [MPS]

The Motivation Equation

We can use MPS to assess the results of the job diagnostic survey which measures each of the five job characteristics individually, while the motivation equation lumps them all together to produce a single score for a jobs motivating potential.

MPS can be thought of as the average of skill variety, task identity, and task significance, multiplied by feedback and autonomy. It is the key aspect of the job characteristics model and we can use it to effectively diagnose and optimize a job.

By tweaking with a job's design, you moderate it's characteristics which, in turn, influence the three psychological states. When you are able to achieve a high MPS, you maximize the employee experience, which in turn maximizes desired outcomes.

In practice, the job optimization cycle looks like this:

- Step 1: Worker fills out the job diagnostic survey

- Step 2: Individual scores for each job characteristic are measured

- Step 3: MPS is calculated from individual scores

- Step 4: Based on results, adjustments are made to job design

- Step 5: Repeat [giving ample time to adjust before surveying again]

Running the Diagnostics

If we want to improve the motivating potential of a job, we need to focus on the individual characteristics first. Because each person who works a job has different motivational needs, we should do this on a case-by-case basis.

It is important to understand that MPS is meant to be used comparatively. That is, there are no "good" or "bad" scores–only ways we can improve. For this reason, it makes sense to look at individual scores for each job characteristic as well as overall MPS.

It is also worth using MPS comparatively between and within teams of varying R&R[2] to get a more holistic understanding of job design in your org.

Always remember to keep in mind the role that individual psychological differences play here–just because one person is highly motivated in a job does not mean another person will be too.

Ultimately, the individual scores are where you want to focus when trying to make improvements to a particular job. And if you do [and you should] assess MPS across teams, the results from one job will help you understand another.

For example:

- What about role x grants a high skill variety score, while role y's is so low?

- What aspects of role x could I bring into role y to improve skill variety?

This process of assessing, adjusting, and re-assessing is the job optimization cycle I mentioned earlier. As you iterate through the job design/redesign process, you eventually find yourself at a place of balance.

Of course, balance isn't always the goal. Depending on the role and level in the organization, you may want to maximize certain job characteristics over others, simply because of the nature of the kinds of people that fill those roles. Maybe you know that Sr. Engineers are much more likely to be 10x engineers with the right job design, so you focus on high task significance and autonomy for them while focusing on feedback for more junior folks.

Whatever it is you are optimizing for, you'll first need to measure your baseline. For that, the motivation equation is the perfect tool.

Footnotes

- In a 2016 study of 181 healthcare workers, MPS had a significant positive correlation with organizational commitment.

- Comparing MPS to similar jobs helps you generate a baseline. Comparing jobs with varying roles & responsibilities [R&R] helps you to identify factors that influence job characteristics and psychological states.