Work systems and the extended mind

As it turns out, On information technology was a discussion of the extended mind hypothesis.

This is the idea that the mind is not limited to the inside of the head. But rather, we leverage systems and tools to extend our minds outside of the head, into the world.

Consider the following thought experiment:

Suppose you and a friend are meeting for coffee. Your friend remembers that the coffee shop is on Smith Street, so he hops in his car and drives himself over. You've been to the coffee shop before, but it's been a while, so you'll need to look it up on your phone first. Once Google Maps reminds you of its location on Smith Street, you hop in your car and drive yourself over.

Is there any relevant difference between the mental states you and your friend arrived at?

Before answering this, let's first define a mental state: a condition of the mind which has content, typically expressed in "that" statements, corresponding to thoughts and feelings.

For example, the belief that I am writing, the desire that I convey this information clearly, or the intention that I publish this in May.

From mental states, we are able to arrive at a proposition–an attitude, argument, theory, proposal, etc., which may lead to actions[1].

In our thought experiment, both parties arrive at the same mental state–the belief that the coffee shop is located on Smith street. Of course, there are differences in the way that mental state was reached, but that is less a matter of mental state than it is a matter of vehicle.

All mental states need vehicles–a means to arrive at said mental state. In conventional philosophy (i.e., the identity thesis), the vehicles of mental states are neural states. For the extended mind hypothesis, vehicles can exist outside of the mind: a notebook, a smartphone, or another information system.

The extended mind hypothesis says that the vehicle in which you arrive at a mental state makes no difference. All that matters in defining a mental state is that it functions as one. This is known as the parity principle and is a fundamental argument for functionalism.

Functionalism posits that mental states are mental states regardless if they arise from flesh or metal or silicon. This is interesting because it leaves open the possibility that, in the future, machines will have mental states of their own.

Given the recent advancements in computing and artificial intelligence, it is important that we have a philosophy that can account for the possibility of machines not just passing the turning test but, by way of function, have beliefs, desires, and intentions of their own.

If functionalism is true, there is no reason to believe that mental states coming from within the head are fundamentally different from mental states that arise from outside the head. They play the same role in cognition.

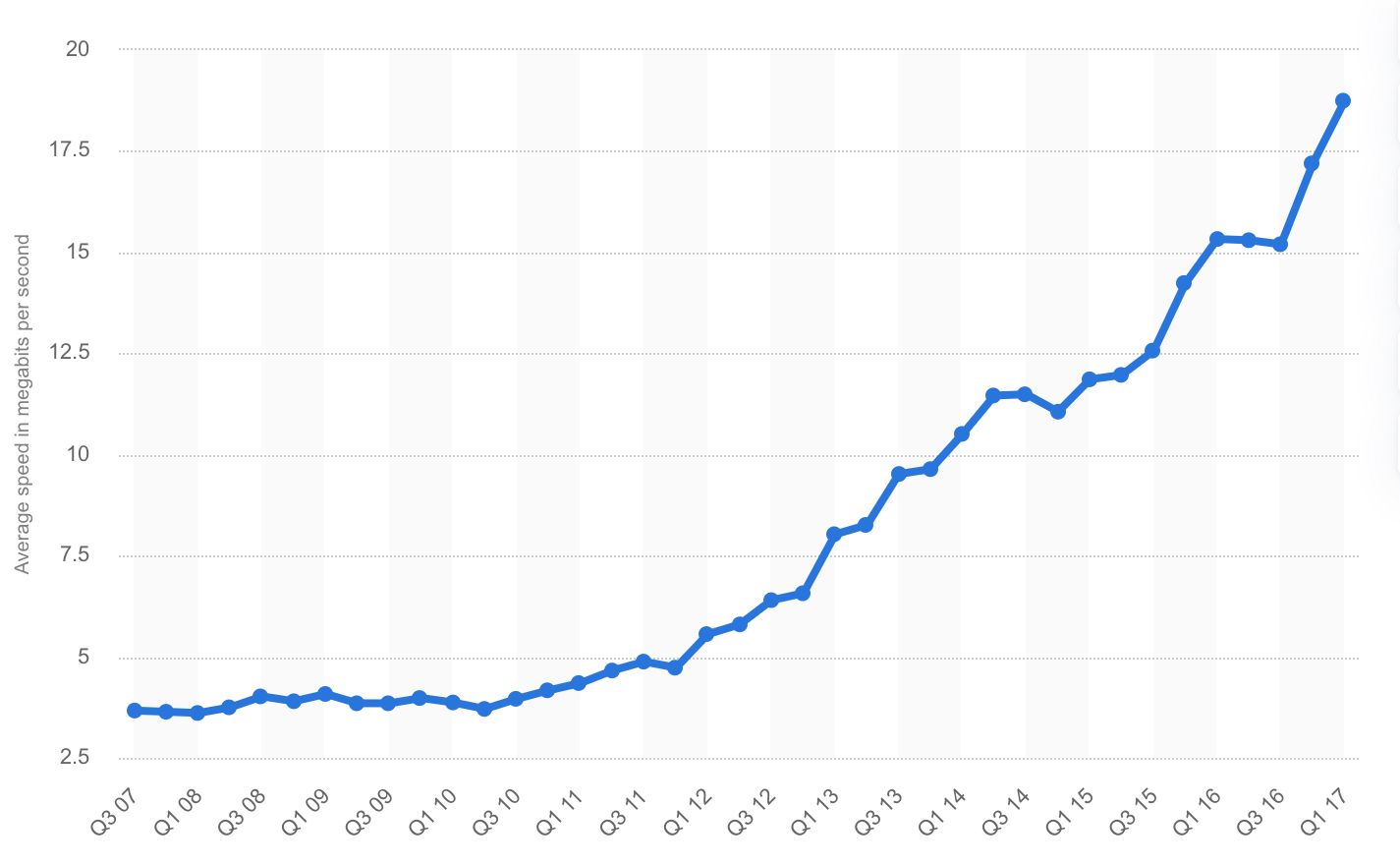

In his paper, Neuroethics and the Extended Mind, Neil Levy goes on to suggest that not all information technologies can be classified as vehicles of mental states. He argues that 1) Wi-Fi isn't always available and 2) the latency between our brains and those systems isn't efficient enough. Yet in the decade since the paper was published, we've significantly reduced that latency.

Starlink satellites will soon be available worldwide with the potential to provide internet to everyone, anywhere. And in the not-so-distant future, we'll experience the world through brain-machine interface technology, where that latency will cease to exist.

Although we aren't there yet, I would argue that information technology today largely serves as a vehicle of the extended mind. It may not serve people of all kinds, in all contexts, but it does for many.

Most of us leverage information systems every day to make decisions about our life and work. I for one, could not do my job effectively without them.

Just like in the thought experiment when you leveraged Google Maps to remember the coffee shop's location, I use Google search to remember syntax for code I write. If my intention is that I have working code, does it matter the vehicle I use to get there?

Now, consider this same idea but at scale: systems of people utilizing information technology as an extension of mind.

Organizations with well-leveraged information systems have the foundations for collective intelligence; an extension of social interactivity and interconnected processes among networks of human nodes. Like an organizational hive mind, the social and technical subsystems[2] of a larger work system have the potential to synthesize.

The most effective organizations in the future of work will learn how to make this happen.

Footnotes:

- Actions are not mental states but are often the result of them.

- The social subsystem refers to the division of labor and methods of coordination used to transform inputs into outputs in an organization. The technical subsystem refers to the tools, systems, and procedures used in that organization's transformation process.