Foundations: what the hell is I/O psychology?

Contents

I. What the Hell is I/O Psychology

II. Layers & Branches

--- i. Work Systems

--- ii. Life-Cycle

--- iii.Reward Systems

--- iv. Influence

III. The Indivudal in the Organization

What the Hell is I/O Psychology?

Googling the definition of I/O psychology returns a new definition for each result. Here are the first three:

The specialty of industrial-organizational psychology is characterized by the scientific study of human behavior in organizations and the work place. - APA

Industrial-organizational psychology is the branch of psychology that applies psychological theories and principles to organizations. - Verywell Mind

[I/O psychology is] the science of human behavior relating to work and applies psychological theories and principles to organizations and individuals in their places of work as well as the individual's work-life more generally. - Wikipedia

Notice how the APA refers to the field as a scientific study, while Verywell Mind references application. And Wikipedia... well, it's a mouthful.

Most of the information out there fails to paint the complete picture. I hope Foundations helps to fill the gaps.

In a nutshell, I/O psychology is the scientific study of organizations as social systems and the human behaviors occurring within them. Still, this is a surface level understanding which doesn't explain it much better.

I/O psychologists apply the scientific method to all facets of work, allowing us to make more informed decisions. While some conduct research, others apply their knowledge as practitioners, utilizing their training in the scientist-practitioner model, which says that psychologists are both practitioners who apply knowledge and scientists who base their actions on research.

I/O psychologists are interdisciplinary generalists. Their speciality, if anything, is in their fundamental understanding of people and systems. They are skilled at reverse engineering complex processes, breaking down the individual tasks and talents required to reconstruct them (a practice formally known as job analysis). Skills like these make for exceptional problem solving.

But of course, there is more to I/O psychology than problem-solving.

Note: I/O stands for industrial/organizational. The difference between the two has become blurred over the years, but if you'd like to read about it, here is a good resource.

Layers & Branches

I find it helpful to think of I/O psychology as having layers (like our planet) and branches (like a tree).

At the core of the study is people. The middle layer is the study of groups. The outer layer, or crust, is the study of organizations. And everything outside that, whether sitting on top or out in the atmosphere, is the social environment. All of these have a sort of hierarchical relationship. From individuals outward towards society.

Because it's a field with lot of breadth, I use branches to represent different sub-disciplines: work systems, life-cycle, reward systems, and influence.

The remainder of this post will be broken down by these branches. Each containing a series of questions reflecting how that branch contributes to the field as a whole, followed by a curated list of resources that can help answer them.

See if you can notice the layers within branches.

Work Systems

Organizations are like complex operating systems, each with their own functions and properties. The work (input) and product (output) are reflective of an organizations production function. Work systems refers to the underlying formulas dictating how organizations structure and operate themselves.

How do you structure an organization to optimize efficiency?

Org design is a topic where there is much to consider, but I think Richard Daft does a great job at laying out the groundwork in, What is the Right Organization Design.

The paper summarizes his larger text, Organization Theory & Design. Which I still find myself referring back to today. Daft breaks down the different types of org structures and their use cases. This is a great read for startups in the high growth stages of the org life-cycle as well as for other leaders thinking of strategically re-aligning their organization.

For another great resource, I recommend this paper on The Science of Organizational Design, which examines the m-form hypothesis using computer simulations to predict its viability.

How do you make teams more efficient?

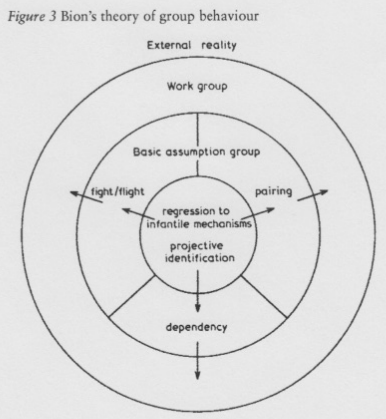

Teams are just glorified groups. If people are the individual building blocks of organizations, teams are the beginnings of structure. There are two theorists who discuss team dynamics that I think are worth mentioning: Wilfred Bion and Bruce Tuckman.

Bion might be one of the most undervalued theorists in psychology. He was to group psychology what Freud was to individual psychology. His book, Experiences in Groups, is a fascinating read. It's quite long so here is a summary.

One of the more pertinent topics to consider is his idea of basic assumption groups, which describes the unconscious mechanisms that predict why some groups perform well and others crumble. You can read more about them in this slightly annotated PDF or in this high-level summary.

A final bit about Bion: he was one of the founders of the Tavistock Institute. A little known organization dedicated to the scientific betterment of human relations. This paper describes what they do.

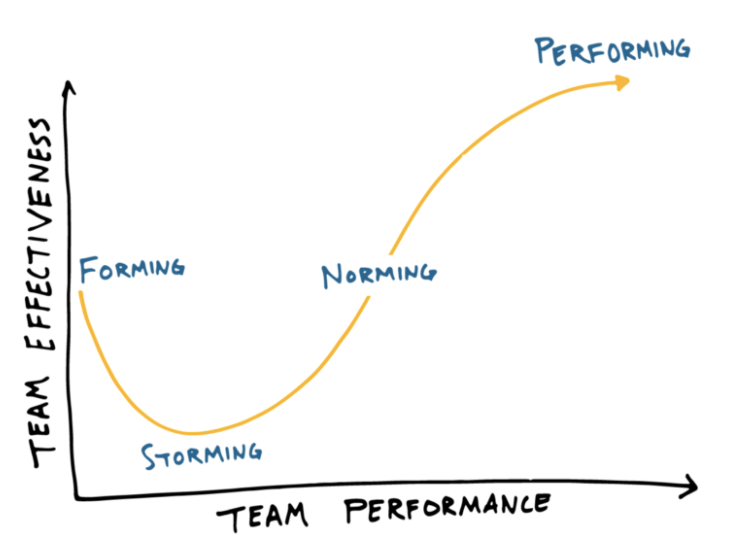

Bion's work can be difficult to grasp. For a more practical approach, I recommend Tuckman's team development model. It focuses on performance and presents five stages of development: forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning.

You can read Tuckman's own article on the model or this summary and visualization of the team effectiveness-performance s-curve:

How should people be managed in an organization?

Effective managers are more than just good leaders. Effective managers understand the limits and potentials of people, including themselves. In this regard, management consultants are functional psychologists, much like what scientific managers should strive to be.

There are some considerations:

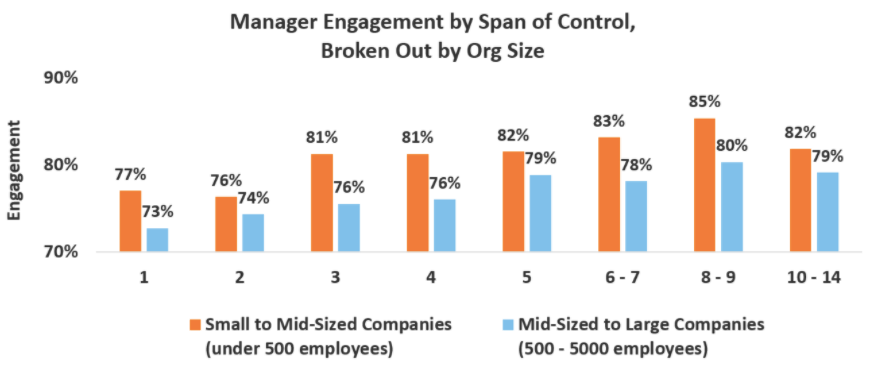

The first is span of control, or the number of direct reports a manager oversees. Span of control is highly correlated with manager engagement, making it an important consideration.

In addition to how many people they oversee, organizations and managers need to decide on tactics. Typically, managers fall into one of two buckets: control or commitment strategists.

The effects of using these strategies can vary drastically from situation to situation. Douglas McGregor presents theory x and theory y to deconstruct those differences.

The final consideration is the psychological contract. This refers to the unspoken set of expectations between two parties. In this case, manager and subordinate. Those in positions of power typically have more control over how the contract is developed, but it is up to subordinates to decide whether or not to accept this authority.

How do you structure the work so it is done most efficiently?

This question gets down to that core level: people.

Richard Hackman and Greg Oldham have well researched this topic and developed the job characteristics model which lays out the five dimensions of a job that should be designed to maximize employee motivation. They are:

- Skill variety: the range of skills required to do a job well

- Task identity: the degree to which the work demands a complete process

- Task significance: the degree to which a job is meaningful

- Autonomy: the degree to which a job offers independence

- Feedback: the degree to which knowledge of performance is received

The model offers a practical framework for designing jobs to be more pleasurable and fulfilling. By increasing job satisfaction and motivation, people naturally perform better.

For a more comprehensive overview, see this Oxford Research Encyclopedia page on Job & Work Design.

How do you make the work itself more efficient?

This question is at the center of what The Scientific Manager is all about. Naturally, I look to Frederick Taylor for answers.

Taylor was an industrial engineer and management theorist known as "the father of scientific management". He believed that by synthesizing aspects of science and engineering, he could uncover the single best way of doing things. However, his approach had one fatal flaw: by treating organizations as machines and workers as cogs in the wheel, it fails to acknowledge the human aspect inherent in all organizations.

Still, Taylor's impact on the business world was massive. Concepts like talent management, performance management, and skill based hiring were all born from Taylor's ideas and remain common practice in organizations today.

Arguably, his most important contribution was his use of the scientific method to study and optimize work. To do this, Taylor pioneered time-and-motion studies (among other innovations) to experiment at work like a true a scientist-practitioner.

For a great summary and discussion of his work I would recommend the first episode of the Talking About Organizations podcast. For a more visual representation, this clip from the movie The Founder does a great job of embodying Taylorism.

Life-Cycle

Organizations are cyclical by nature. Through stages of growth to the flow of people in and out, patterns emerge at all levels. From them we can make predictions, making this an important branch of I/O psychology. Life-cycle refers to the cyclical patterns of change inherent in all organizations.

What are the predictable growth patterns of organizations?

At the organizational layer of I/O psychology, we observe common patterns of change. From the emergence of ideas to the production of MVPs. Founders rise and executive leaders take reign. Soon, processes are put in place and what was once a thriving team of highly engaged entrepreneurs becomes a bureaucratic money machine running on the fumes of its shareholders.

That might be a little dramatic, but history has shown that organizations share familiar cycles. Growth is often accompanied by change, while pivotal turning points ultimately decide the fate of the organization.

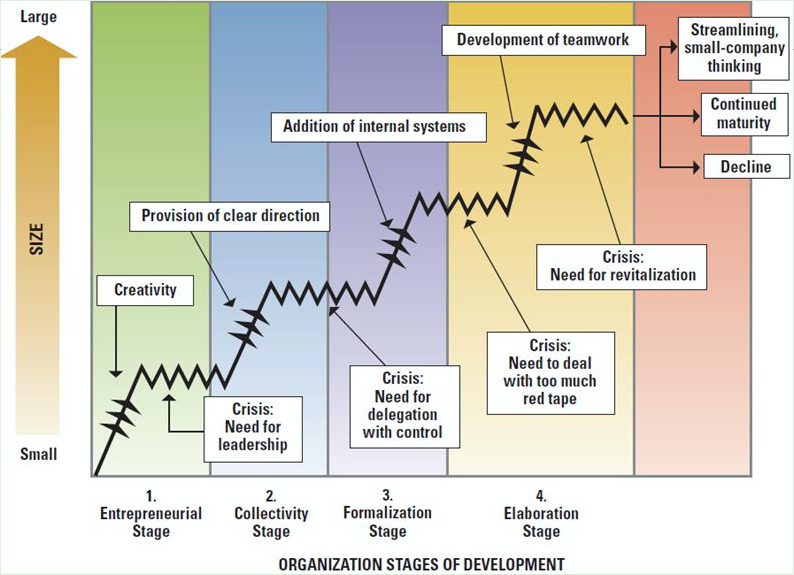

Daft's model of organizational life-cycle presents four stages, each defined by a crisis.

- The entrepreneurial stage: defined by creativity and a need for leadership.

- The collectivity stage: defined by clear direction and a need for delegation with control (management).

- The formalization stage: defined by systems and processes and too much red tape (bureaucracy).

- The elaboration stage: defined by teamwork and a need for revitalization.

Change is inevitable. If an organization's domain is affected (such as with the introduction of new technology) it is adapt or perish. Small company thinking helps, but it is an organization's ability to innovate that prevents decline. These climactic crises at the end of the elaboration stage can result in the formation of new organizations, refreshing the cycle.

For a more comprehensive review of organizational life-cycle, check out this article by Inc.com.

How do you manage the flow of people in and out of an organization?

Retaining good talent means getting the work done. Getting the work done means hiring the right people. Hiring the right people means retaining good talent.

People move in and out of organizations in cycles. The key is to ensure proper filtering:

Keeping the bad ones out and the good ones around.

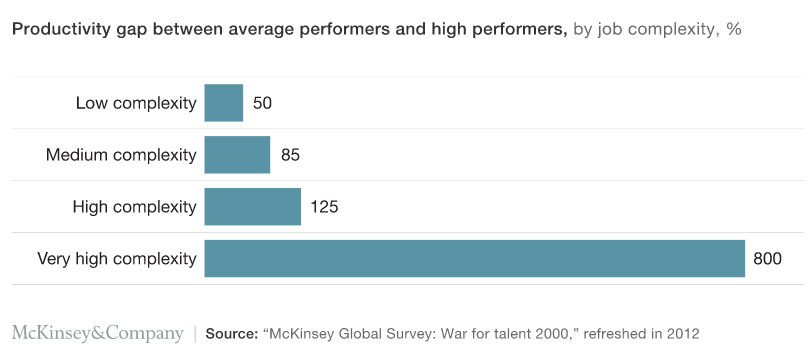

While the 10x programmer may be something of legends, the idea that there is exceptional talent out there is no myth. According to this article by Scott Keller of McKinsey & Company, high performers not only do the best work, but can also be up to 400% more productive than their peers. For high complexity work, this can be as high as 800%.

Though, there is more to talent than productivity. Equally important is how they fit into the bigger picture. Great hires have skills that both complement the team and fill a gap in the organization. This HBR article highlights 7 scientifically backed ways we can work to hire the best talent for the organization.

- Think ahead

- Focus on the right traits

- Don't go outside when you can stay inside

- Think inclusively

- Be data-driven

- Think plural rather than singular

- Make people better

Once people join an organization their paycheck is the bare minimum for keeping them there. Effective organizations understand that retaining talent is a matter of motivation (more on this in reward systems).

Reward Systems

We primarily focus on monetary compensation as the default reward system. Effective organizations know better than that. Reward systems refers to the underlying mechanisms that can make or break a high performance workforce.

How do you motivate people?

When your goal is to compensate someone for their work, you pay them. But when your goal is motivate, monetary rewards miss the mark.

In the marshmallow experiment, Tom Wujec found that offering a $10,000 reward to the winner made everyone perform significantly worse. Which begs the question:

How do you reward people for their work to keep them motivated?

For this, we should consider three Motivation theorists: David Mclelland, Abraham Mazlow, and Frederick Herzberg.

McClelland's three needs theory says that there are three types of people: those that are achievement-oriented, power-oriented, or social-oriented. Each type describes what motivates them.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs says we have a hierarchical set of needs. Beginning with physiological needs upwards to psychological needs and ultimately, to self-actualization. We cannot reach self-actualization without first reaching every subsequent need before it.

Herzberg's hygiene factors says that satisfaction and dissatisfaction are not sides of the same coin. One can simultaneously be satisfied and dissatisfied. He describes the difference as growth vs hygiene factors. Hygiene factors are things you expect from a job which keep you from being dissatisfied, such as safe working conditions. Improving these factors does not increase motivation, but lacking them is a substantial demotivator. Growth factors, in contrast, won't demotivate, but improving them will increase motivation, such as from achievements or personal development.

To put it all into perspective, here's a great article comparing the three theories.

Influence

There is a constant exchange of energy between the individual and the organization. The degree to which one can change the other is relative to this exchange. Influence refers to the psychological and sociological impacts of social systems with shared goals and production systems, i.e., organizations.

To what degree do employees have influence over the organization as a whole?

I like to think of employee networks as the individual atoms that make up a compound. The addition of new employees can strengthen the organization, weaken it, completely change it, or do nothing at all.

Organizational culture reflects the sum of employee consciousness. Certain employees in particular (i.e., leaders) hold more or less weight in this equation. That weight is a matter of influence and authority, maximized by the efficient development of psychological contracts. Poorly developed psychological contracts lead to poorly influenced employees who, in reality, hold the power to decide whether or not to accept that authority.

How do you define Culture? How do you change it?

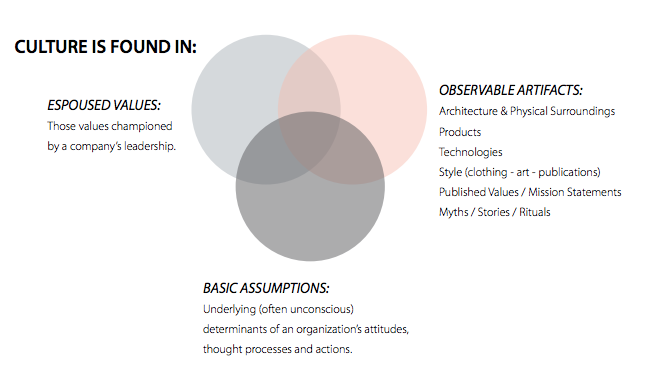

Corporate culture is an abstract concept. Defining it requires considering outside disciplines such as anthropology to understand its origins. The foundational model for organizational culture comes from Edgar Schein of MIT’s Sloan School of Management:

Read about the anthropological origins of culture and Schein's model here.

What you'll realize is, changing culture is even harder than defining it. Steve Denning, Author of The Age of Agile tells the history of the World Bank as an interesting case study for organizational culture change. David Rock, founder of the NeuroLeadership Institute, gets right to the point.

Does the ideal or optimal culture exist?

The world is changing faster than ever. Technological growth is moving at an exponential rate. Keeping up requires resourcefulness and resilience. But more importantly, it requires a cultural shift towards learning.

The learning organization is a term coined by Peter Senge which describes the idea that the most efficient organization is one that is able to continually adapt to changes in the environment.

Learning organizations do this by creating a learning culture: One that encourages and rewards employees for being resourceful, seeking new knowledge, and sharing that knowledge with the rest of the organization.

I love this near 30-year-old HBR article that describes the learning organization because it's aged so well.

Fostering a learning culture is hard. Organizational leaders can influence change, but first they need the authority to do so.

How do you define and distribute authority in the workplace?

There are two theorists on authority we should consider: Chester Barnard and Max Weber.

Barnard says that authority lies with the person receiving the order, not the one giving it. It is the receiver who must decide whether or not to obey the order. Hence why this theory is sometimes referred to as bottom-up or acceptance theory of authority.

Additionally, there are four conditions which must be met for an authority to be accepted:

- The person receiving the order is able to fully interpret the communication.

- The person receiving the order believes that the communication is consistent with the objectives of the organization.

- The person receiving the order believes that the communication is consistent his/her personal objectives.

- The person receiving the order is physically and mentally capable of accepting the communication.

If any of these conditions are not met, the order will be rejected.

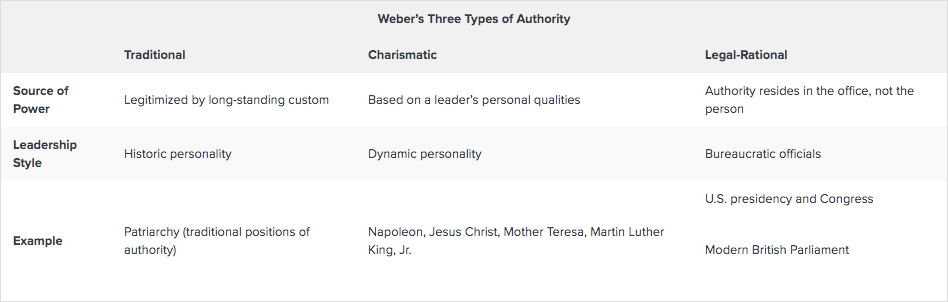

Weber says there are three types of authority: traditional, charismatic, and legal-rational.

This article from the University of Minnesota's open library, gives an overview of Weber's authority typologies.

It is important to be able to distinguish between power vs authority, as well as what the different types of authorities are, to understand how different types of leaders can influence an organization. While certain types of authorities exist, these do not define the behaviors of the leader. They merely describe the grounds in which their authority is based.

What makes a good leader and how do we choose them?

Kurt Lewin was one of the first psychologists to develop a theory on leadership. He came up with three foundational styles: autocratic, democratic, and laissez-faire.

Read more about them here.

Lewin was a pioneer. These three styles influenced many of the leadership typologies we consider today (e.g., servant, transformational, transactional, situational, etc.). But since his time, there have been more theories of leadership than I can count on my fingers.

For a more comprehensive guide to leadership theory, this article from Western Governor University hits the nail on the head.

I will dive much, much deeper into leadership in the future.

As a final touch, consider this 2007 article on the psychology of leadership from the Scientific American. Here is a quote from the final paragraph:

"Either way, the development of a shared social identity is the basis of influential and creative leadership. If you control the definition of identity, you can change the world."

The Individual in the Organization

What I find funny about I/O psychology is that in the opportunities that I do have to talk about it, a common response is that it makes a lot of sense; that it seems intuitive, almost obvious.

But that's just it: the answers to some of the biggest questions in business are surprisingly human!

Our mental models, developed from our individual experiences, have instilled certain biases that are difficult to overcome. This is why diversity is so important for organizations. More similar minded individuals means less questioning of ideas and decisions. Each individual in an organization is in a position to make a difference in someone else's life. We should make it a point to not let our biases get in the way of that.

Regardless of the position you hold, executives down to individual contributors all work with people. We ought to bring our best selves to work because, somewhere along the way, we may have an interaction with someone that changes the course of their lives or careers. Maybe it's selling them a life saving product, maybe it's giving them a job, or maybe it's taking one away. It could even be as simple as making a good impression on a perspective client; an impression that they remember when deciding to sign a multi-million dollar deal. We ought to pursue new ways of thinking so that the effect we have on other people's lives is net positive when our careers are over.

As knowledge workers, our effect sizes are rarely opaque. Whatever your place in the organization, understand that mental models shape your every action. To do better, we must pursue new ways of thinking, ask the questions no one else is asking, and experiment with work.

The duty of the individual in the organization is not to be a cog in the wheel as Taylor assumed 100 years ago. It is to challenge oneself and ones peers to be the seeds of progress.

"Business is the only institution that has a chance, as far as I can see, to fundamentally improve the injustice that exists in the world. But first, we will have to move through the barriers that are keeping us from being truly vision-led and capable of learning." - Edward Simon, former president - Herman Miller, 1990

Capitalism has created something few saw coming. A paradox in which we have allowed organizations to amass great power by a factor of what they produce. The more an organization is able to produce, the more they are able to turn a profit. And in a society run by capitalists, profit equals power. If only we had a way to leverage this power for the greater good...

The problem is organizations are caught in profit loops, consequentially focused on turning a profit rather than bringing good to the world. Somewhere along the way, we have confused those two things.

You don't have to convince a CEO to stop making money. In fact, you never will. You can however, leverage your understanding of human nature; begin to understanding work systems, life-cycles, reward systems, and influence; remember that there are levels to organizations, and that problems must be addressed at their respective level, whether it is individual, group, or organization. And most importantly:

"Research your own experience. Absorb what is useful, reject what is useless and add what is essentially your own." - Bruce Lee

Thanks for reading!

The Scientific Manager is the reinvention of scientific management in age of technology. Join like-minded individuals interested in learning about how they can synthesize aspects of psychology and engineering to work smarter and maximize their potential.